This information is only a guide and should not replace information supplied by your anaesthetist. If you have any questions about your anaesthesia, please speak with your treating specialist.

Different kinds of anaesthesia

Duration of anaesthesia

Risks and complications

- What are the risks of having anaesthesia?

- Could I react to an anaesthetic drug?

- Will I experience nausea or vomiting?

Awareness

Regurgitation and aspiration

Fasting

Taking medications

Smoking and anaesthesia

Herbal and dietary supplements

Blood transfusions

Anaesthesia and the elderly

Obesity

Epidurals and childbirth

- How common is it for women to have an epidural in labour?

- How do epidurals compare with other options in terms of providing pain relief?

- What is the optimal timing of getting an epidural?

- Will I need to have a caesarean section if I have an epidural?

- Will an epidural affect my baby?

- Can epidurals cause back pain?

- What are the risks associated with epidural?

- How long will post-dural puncture headache last for and what are the treatment options?

Caesarean section

- If I had an epidural put in for labour pain, and I require a caesarean section, what happens to the epidural?

- How will the anaesthetist make sure that I won’t feel pain during the caesarean section?

Spinal and epidural block

What are the different kinds of anaesthesia?

These can be broadly divided into local anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia (nerve blocks, epidural, spinal), sedation and general anaesthesia.For some types of surgery there are several anaesthesia choices available. You need to be assessed by the anaesthetist who, in consultation with you and the surgeon, will determine the appropriate type of anaesthesia.

Local anaesthesia

Local anaesthetic is injected under the skin and the tissues below the skin around the area to be operated on. It may be the only type of anaesthesia used or it may be combined with sedation or general anaesthesia, depending on the extent of the operative area and the duration of the surgery. Local anaesthesia is usually an option for minor surgery, such as toenail repair, skin tear or a cut to remove something. If the area to be operated on is infected it may not be appropriate to use local anaesthesia.

Regional anaesthesia

Regional anaesthesia involves the injection of local anaesthetic around major nerve bundles supplying body areas such as the thigh, ankle, forearm, hand and shoulder. Regional anaesthesia may be performed using either a nerve-locating device such as a nerve stimulator, or ultrasound, which is a painless procedure used to demonstrate internal body structures using sound waves to create an image. These may help to more precisely locate the selected nerve(s) and deliver the drugs with greater accuracy. Regional anaesthesia may be the only anaesthesia needed for surgery or may be combined with general anaesthesia. Once the local anaesthetic is injected, you may experience numbness and tingling around the operative area. You may also notice that moving the affected area such as arm or leg(s) may become difficult, if not impossible. This indicates that the appropriate nerves have been anaesthetised or “blocked”.

Sedation

There are two types of sedation. Procedural sedation is used for procedures where general anaesthesia is not required and allows patients to tolerate procedures that would otherwise be uncomfortable or painful. It may be associated with a lack of memory of any distressing events. Conscious sedation is defined as a medication-induced state that reduces the patient’s level of consciousness during which the patient can respond purposefully to verbal commands or light stimulation by touch.

General anaesthesia

General anaesthesia produces a drug-induced state where the patient will not respond to any stimuli, including pain. It may be associated with changes in breathing and circulation.

How long will the local anaesthetic effect last?

This depends on the type of local anaesthetic used and the region of the body into which it is injected. Typically, anaesthesia can last several hours but occasionally it can last up to a day, after which it will begin to wear off. You will notice either a return of movement or increase in pain, which is when you will need to take or be given pain relief. This can be done in tablet form or by injection into a muscle or vein. The risks and complications of this anaesthesia are discussed below.

What will I feel during anaesthesia?

All types of anaesthesia are designed to reduce or remove feeling in the part of the body where the procedure is happening. If conscious sedation is used then patients are able to respond purposefully to verbal commands or light touch. A variety of medications and techniques are available for procedural sedation and/or pain relief. The most common medications given into a vein are benzodiazepines (such as midazolam) for sedation and opioids (such as fentanyl) for analgesia, which decrease the perception/feeling of pain.

Deep levels of sedation, where consciousness is lost and patients respond only to pain, are associated with reduced ability to maintain an open airway. The anaesthetist will relieve any difficulty with breathing or changes in heart function. Having general anaesthesia involves the patient being put into a medication-induced state where the patient does not feel pain, and may be associated with changes in breathing and circulation. Under general anaesthesia, a patient is in a state of carefully monitored unconsciousness.

What are the risks of anaesthesia?

While Australia and New Zealand are among the safest nations in the world in which to have anaesthesia, receiving multiple medications and altering normal human body function carries risks, some of which may be potentially life threatening. Risks and side effects include nausea and vomiting, physical injuries, reactions to drugs, awareness and even death. If you are concerned about these side effects please discuss them with your anaesthetist.

While Australia and New Zealand are among the safest nations in the world in which to have anaesthesia, receiving multiple medications and altering normal human body function carries risks, some of which may be potentially life threatening. Risks and side effects include nausea and vomiting, physical injuries, reactions to drugs, awareness and even death. If you are concerned about these side effects please discuss them with your anaesthetist.

Physical injuries

Damage to teeth occurs in fewer than 1 in 100 general anaesthetic cases (Jenkins K, Baker AB. Consent and anaesthesia risk. Anaesthesia 2003: 58: 962-84). This usually occurs during a process known as laryngoscopy (inserting an instrument into the mouth), when a breathing tube is inserted through the vocal cords in your airway while you are asleep or if a plastic sucker has to be used to clear fluid in your mouth. The anaesthetist will take care during the anaesthesia and will examine your mouth prior to the operation and document the status of your teeth, including presence of caps, crowns, loose teeth or dentures.

Sore throat

Sore throat may occur in up to 45 per cent of patients having anaesthesia requiring a breathing tube known as an endotracheal tube, and in 20 per cent of patients when a laryngeal mask, which is a mask and tube that is inserted into the back of the throat, is used. The sore throat usually gets better by itself and may take a few days. Persistent sore throat may need to be referred back to the anaesthetist or reviewed by your doctor.

Nerve injuries

Nerve injury (damage to nerve fibres) following nerve blocks (regional anaesthesia) occurs in approximately 0.02 per cent or 1 in 500 cases (Jenkins K, Baker AB. Consent and anaesthesia risk. Anaesthesia 2003: 58: 962-84). Risks associated with epidurals are discussed under regional anaesthesia.

Blindness

All complications are unfortunate and this complication is extremely rare, occurring in approximately one in 1,250,000 anaesthetics (Taylor TH. Avoiding iatrogenic injuries in theatre. BMJ 1992: 305: 595-6). Patients who are at a higher risk of blindness include smokers and those with high blood pressure or diabetes. Patients undergoing spinal and cardiac surgery involving cardiopulmonary bypass are at a higher risk than patients undergoing other types of surgery. If you have any of these conditions, discuss any concerns with your anaesthetist before your procedure. If you develop visual disturbance after your operation you should seek urgent medical attention.

Death

Death related to anaesthesia is extremely rare. Type of surgery (in particular if the surgery is an emergency such as for major trauma), underlying medical condition, physical status, and age all impact on the rate of death. According to the American Society of Anaesthetists (ASA) classification system, which is based upon the overall health of the patient, for a healthy patient (known as ASA 1) undergoing surgery the incidence of death is about one in 100,000. If combined, the incidence of death of patients with all different physical conditions, including those that are not expected to survive with or without the operation (ASA 4), is one in 50,000. (Contractor S, Hardman JG, Injury during anaesthesia, CEACCP, Volume 6, Number 2 2006)

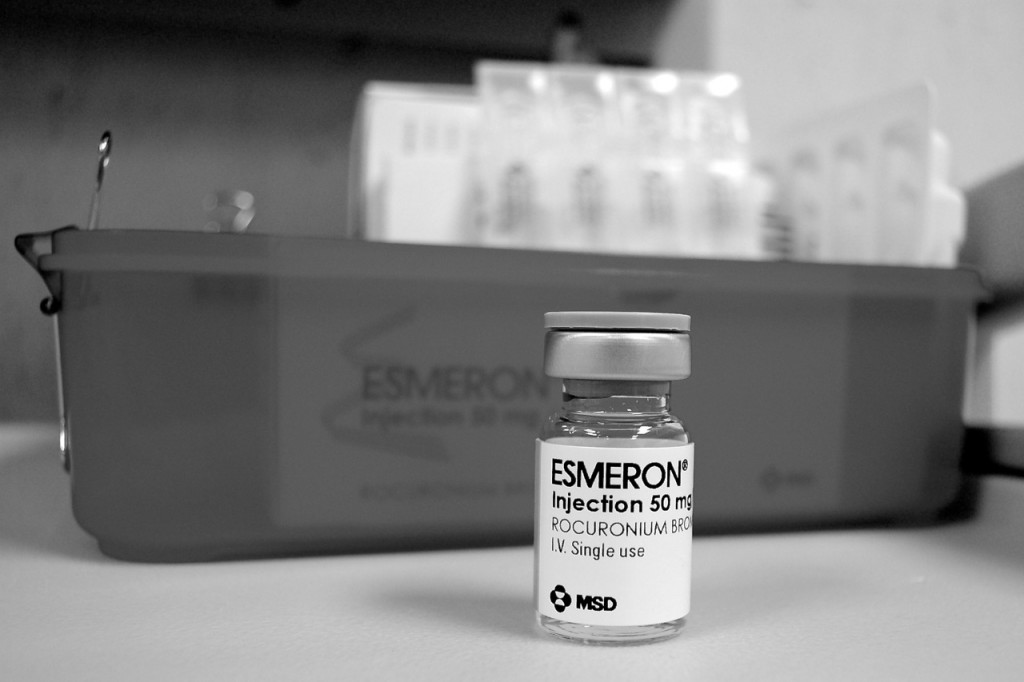

Could I react to an anaesthetic drug?

It is possible to have an allergic reaction to medications given as part of anaesthesia.

It is possible to have an allergic reaction to medications given as part of anaesthesia.

The reaction varies from a mild allergic reaction, such as a rash, to a life-threatening reaction called anaphylaxis, which is a severe life-threatening allergic reaction. The incidence of anaphylaxis reactions to anaesthetic agents in Australia is 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 20,000. Neuromuscular (nerve and muscle blocking medications are responsible for 70 per cent of the life-threatening allergic reactions during anaesthesia. In 80 per cent of reactions to these medications, there had been no previous history of use. Antibiotic medications and latex (rubber) are the other common causes of allergic reaction. Penicillin is the most common antibiotic to cause an allergic reaction. It is important that you tell your anaesthetist if you have experienced an allergic reaction to any medications in the past.

Will I experience nausea or vomiting?

In the past, nausea or vomiting were relatively common after general anaesthesia however with new and improved anaesthesia medication and delivery systems, and appropriate use of anti-nausea medication, there has been a reduction in the number of patients experiencing these symptoms. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) occurs in 20 to 30 per cent of the general surgical population and in up to 70 to 80 per cent of high-risk surgical patients. Risk factors for PONV can be divided into three categories:

Patient-specific risk factors

- Female gender, non-smoking status, history of PONV/motion sickness.

Anaesthesia risk factors

- Use of vapour anaesthesia.

- Use of nitrous oxide (gas).

- Use of intraoperative and postoperative opioid medications such as morphine.

Surgical risk factors

- Duration of surgery (each 30 minute increase in duration increases PONV risk by 60 per cent).

- Type of surgery, for example laparoscopy (key hole), gynaecological (reproductive), ophthalmologic (eye surgery) and breast.

- Some studies report migraine, youth, anxiety and patients with a low ASA (American Society of Anaesthetists) risk classification as independent predictors for PONV, although the strength of these factors varies from study to study (8,9).

- Longer procedures under general vapour anaesthesia accompanied by longer exposure to the vapour anaesthesia and increased postoperative opioid consumption are associated with an increased incidence of PONV.

- Use of regional anaesthesia is associated with a lower incidence of PONV than general anaesthesia in both children and adults.

It is important that you notify your anaesthetist if you have experienced nausea and vomiting after a previous anaesthesia. There are measures that can be taken to minimise the chance of this happening again.

I am frightened that I may be aware during an operation. Is that possible?

This experience, known as “awareness”, is one of the biggest concerns for patients about to undergo surgery. Though it may worry patients, this condition can be almost entirely eliminated by the anaesthetist, with fewer than 1 in a 1000 patients remembering any part of their operation and most of these not recalling any pain.

This experience, known as “awareness”, is one of the biggest concerns for patients about to undergo surgery. Though it may worry patients, this condition can be almost entirely eliminated by the anaesthetist, with fewer than 1 in a 1000 patients remembering any part of their operation and most of these not recalling any pain.

Conscious awareness without recall of pain is more common; it has been estimated at 0.1 to 0.7 per cent of cases (1 in 142 to 1 in 1000). Some operations are associated with a higher risk of awareness than others. They include cardiac surgery, emergency surgery, surgery associated with significant blood loss and caesarean section.

Specialised monitoring equipment is available to assist anaesthetists to assess the depth of anaesthesia. Such equipment includes processed electro-encephalography such as Bispectral Index Scale (BIS) and Entropy, which record electrical wave patterns in the brain and assign a score which reflects the depth of unconsciousness. These monitors have been shown to reduce the incidence of awareness, particularly in high-risk cases.

What is regurgitation and aspiration?

Regurgitation is a passive process whereby the stomach contents are brought up into the oesophagus (food tube). It may occur at any point during anaesthesia. Aspiration is the inhaling of those contents into the lungs, where the acidic contents may damage the lung tissue.

Several factors work towards regurgitation and aspiration happening, including emergency surgery, light anaesthesia, upper and lower gastrointestinal (gut) disease, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux (heartburn), impaired consciousness level and hiatus hernia of the stomach. Trauma, labour and opioid medications slow down stomach emptying.

The anaesthetist will account for these factors and may perform a “rapid sequence induction”. In this procedure, 100 per cent oxygen is administered for several minutes before administering the drugs that put you to sleep. This fills your lungs with 100 per cent oxygen. The assistant to the anaesthetist will lightly press on your throat before any loss of consciousness to prevent any substances coming up from the stomach (regurgitation) and into the throat form where they can then be inhaled into the lungs (aspiration).

Do I need to fast prior to surgery?

Yes, fasting (not eating or drinking) is mandatory prior to sedation or a general anaesthesia to minimise the risk of regurgitating the stomach contents. Fasting reduces the risk of regurgitation and aspiration and damage to lungs by acid if regurgitation does occur. Each hospital has its own instructions that you should follow.

Yes, fasting (not eating or drinking) is mandatory prior to sedation or a general anaesthesia to minimise the risk of regurgitating the stomach contents. Fasting reduces the risk of regurgitation and aspiration and damage to lungs by acid if regurgitation does occur. Each hospital has its own instructions that you should follow.

The following fasting guidelines are recommended by ANZCA, although each anaesthetist may modify these according to individual requirements.

- For healthy adults having elective (planned) procedures, limited solid food may be taken up to six hours prior to anaesthesia and clear fluids totalling not more than 200mls per hour may be taken up to two hours prior to the patient receiving an anaesthetic. Clear fluids may include water, black tea or black coffee, but NOT milk. Chewing gum and chewing tobacco should be treated as food, as they both increase gastric secretions.

- For healthy children over six weeks of age having elective (planned) procedures, limited solid food and formula milk may be given up to six hours, breast milk may be given up to four hours prior and clear fluids up to two hours prior to the child receiving an anaesthetic.

- For healthy infants under six weeks of age having an elective (planned) procedure, formula or breast milk may be given up to four hours and clear fluids up to two hours prior to the infant receiving an anaesthetic.

What medicines should I stop or take prior to having surgery?

As a general rule you should take your usual morning medications with a sip of water on the morning of the operation unless instructed otherwise by the anaesthetist.

It is important to cease some medicines prior to surgery, including blood-thinning drugs, also known as anti-platelet drugs (aspirin and clopidogrel), and anticoagulants such as warfarin or pradaxa. If a heart specialist has prescribed them, then he or she should review you prior to surgery or at least be notified that you are having surgery. The decision about ceasing medications should be made primarily by the prescribing doctor in consultation with the anaesthetist and your treating surgeon. It is vital that you do not stop taking these medications without specific instructions on when to stop and restart them and whether any other drugs such as clexane in the case of warfarin cessation needs to be taken in the period that these drugs are stopped.

Other medicines that must be adjusted or stopped include those for diabetes. These include various types of insulin or medicines taken by mouth to lower blood-sugar level including metformin (DiaforminR, DiabexR) and glicalizide (DiamicronR). Seek instructions from your anaesthetist or diabetes specialist as to when to stop and resume taking these medicines prior to surgery. This will depend on whether you have type 1 (insulin dependent) or type 2 diabetes (non insulin-dependent diabetes). The timing of your surgery and your blood glucose is controlled.

Does smoking have an impact on anaesthesia?

Smoking not only has harmful effects on general health but can also increase the risk when having anaesthesia and surgery. Smoking is associated with heart disease, peripheral vascular (blood vessel) disease and multiple types of cancer, including lung, throat, and oesophagus (food tube) and bladder cancer. It can also cause emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

ANZCA recognises that tobacco smoking is addictive and can damage both the health of smokers and those passively exposed to tobacco smoke. The College supports all measures to decrease tobacco consumption and involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke including passive smoking.

Nicotine increases the heart rate, heart pumping, blood pressure, and blood vessel narrowing. Some of these adverse effects may improve after 12 to 24 hours of abstinence.

Smokers have an increased production of mucous, which can clog up the airways. They also have increased sensitivity of the airways, which makes the airways more prone to narrowing during anaesthetic. This airway narrowing impedes delivery of oxygen and can be life threatening. This improves one month after smoking is stopped with further improvements up to six months.

Smokers have a decreased ability to carry oxygen in the blood, however ceasing smoking for more than 12 hours greatly improves the ability of the blood to carry oxygen.

There is also evidence of increased respiratory complications during and after general anaesthesia in children exposed to environmental tobacco smoke. Surgical wound complication rates are higher in smokers, particularly following plastic and reconstructive surgery, bone surgery, bowel surgery and microsurgery. Smoking has adverse effects on the blood flow to tissues that may impair wound healing. Smoking is not be permitted within 12 hours of surgery.

Can I take herbal and dietary supplements?

The use of herbal medicines is common. Herbal medicine is defined as a plant-derived product used for medicinal and health purposes; commonly used herbal supplements include echinacea, garlic, ginseng, ginkgo biloba, St John’s wort and valerian.

The use of herbal medicines is common. Herbal medicine is defined as a plant-derived product used for medicinal and health purposes; commonly used herbal supplements include echinacea, garlic, ginseng, ginkgo biloba, St John’s wort and valerian.

Herbal medicines can have a variety of effects on surgery and interact with anaesthetic drugs. Ginkgo, ginseng and garlic all impair blood clotting and promote excessive bleeding. Prolongation of action of anaesthesia drugs can occur with valerian and St John’s wort. Herbal dietary supplements should be stopped two weeks prior to surgery.

Fish oil supplements are also popular as a dietary supplement. They have potential in reducing cholesterol and hence may reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. They also have anti-inflammatory properties and may be used to treat arthritis. The Therapeutic Goods Administration says that omega 3, which is found in fish oil, has no effect on bleeding and can be continued before surgery.

What are the risks of blood transfusion?

Certain types of operations are associated with a greater chance of the patient requiring a blood transfusion, including coronary artery bypass surgery, prolonged orthopaediac (bone) operations (in particular spinal surgery such as surgery for scoliosis (curves in the spine), caesarean section in patients with placenta attachment difficulties called accretta and percretta, and surgery for multiple trauma.

There are a number of possible risks and adverse reactions to blood transfusions. Some of them are the result of interaction of the body’s immune system with components of blood and some are due to factors including the transmission of infectious diseases. Having a blood transfusion is very safe because the Australian Red Cross Blood Service conducts routine screening tests on all donor blood. If you would like to know more, please visit the Australian Red Cross Blood Service website.

The risk of allergic reaction such as wheeze or a rash is about 1-3 per cent. It is treatable. The risk of anaphylaxis (a severe life-threatening allergic reaction) is one in 20,000 to one in 170,000. Further information is available here.

Australia and New Zealand have among the safest blood supplies in the world with the risk of transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV estimated at less than one in one million. Further information is available here.

Are there special considerations regarding the elderly having anaesthesia?

Elderly patients differ from younger patients in numerous ways and this affects the way the anaesthesia is administered the possible complications and problems that may occur during and after surgery. Elderly patients are at an increased risk of illness or disease and death associated with anaesthesia and surgery (Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia).

Elderly patients have a higher prevalence of certain medical conditions and co-morbidity (multiple conditions). These include heart disease, cerebrovascular disease (stroke), hypertension (high blood pressure) and kidney impairment. This impacts on the conduct of the anaesthesia, medication doses and care of the patient post-operatively. Elderly patients also may be taking medications that will need careful review to ensure they do not interact with the anaesthetic drugs. Patients with significant heart disease will require monitoring in a high dependency or intensive care unit. They will require review by a heart specialist prior to having surgery.

Surgery has a major physiological impact in the body in terms of stress response. In elderly patients, these responses may have a significant impact. For example, the increased release of adrenaline increases the workload of the heart. The blood becomes stickier. For patients with underlying heart disease who have narrowed coronary arteries, it may be detrimental to make the heart work harder.

The elderly have lower requirements for narcotic analgesics and sedatives and are more susceptible to depression of conscious level and breathing. (Oxford Handbook)

Temperature regulation is impaired making the elderly more prone to hypothermia (cold temperature). Postoperative hypothermia causes shivering, increasing work on a potentially over-worked heart, putting the patient at risk of suffering a heart attack.

The immune system in elderly patients also is not as effective as in the younger population. This makes the elderly more prone to hospital-acquired and surgical infections. The elderly are also at a higher risk of postoperative confusion. Some of the causes may be reversible, however in a small percentage of patients the confusion persists long term (greater then one year). Your anaesthetist is trained to anticipate, detect and treat all these issues.

What effect does obesity have on anaesthesia?

Obesity is defined as body mass index (BMI) greater than 30kg/m2 and poses a number of problems for anaesthesia. Firstly, obesity is associated with high blood pressure and heart disease. Heart disease may be secondary to coronary artery disease or due to enlarged heart with reduced function. Secondly, oxygen delivery to tissues is decreased in obese patients, which makes obese people more prone to oxygen lack if there are additional difficulties in delivering oxygen to them. Thirdly, obesity may be associated with hiatus hernia of the stomach and there is a higher risk of regurgitation and aspiration. Obtaining intravenous access and performing regional anaesthesia may be difficult. For these and other reasons, it is advisable for patients who are overweight or obese to lose weight prior to elective surgery.

If significant weight loss is not possible, even small weight loss is beneficial. Where patients are able to do so, light exercise, such as a 30 minute walk each day before surgery, will be helpful and make postoperative recovery easier for the patient. You can start with walking 10 minutes each day and increase to 20 minutes per day and then achieve 30 minutes per day.

How common is it for women to have an epidural in labour?

Regional anaesthesia (epidural, combined spinal-epidural or spinal) is used in approximately one third of labouring women (Pregnancy outcome in South Australia 2005, Adelaide Pregnancy Outcome Unit, Adelaide, South Australian Department of Health. Chan A, Scott J, Nguyen AM, & Sage L 2006).

Twenty five per cent of women in the United Kingdom and 66 per cent of women in the United States receive epidural analgesia in labour. In some European countries the number is as high as 98 per cent. (Differences in management and results in term delivery in nine European referral hospitals: descriptive study. European J Obstetrics Gynaecology Reproductive Biology: 2002; 103:4-13)

How do epidurals compare in terms of providing pain relief with other options?

Epidurals are by far the most effective pain relief available to women in labour, though other options are available when an epidural is contra-indicated or otherwise unavailable. (Current opinion in Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2001, 13:583-587).

What is the optimal timing of getting an epidural?

Should women wait until they are far into labour before asking for an epidural? There used to be a commonly held belief that women in labour should wait until the cervix was 4cm dilated before receiving an epidural to reduce the risk of having a caesarean section (Halpern S, Abdallah F, Effect of labor epidural analgesia on labor outcome. Current opinion in Anaesthesiology: 23: 317-323, 2010). Numerous studies demonstrate that early placement of epidurals does not increase the rate of caesarean section. The article above concluded there is no need to deny women in labour adequate pain relief if required. There are a variety of factors that will determine the timing of the epidural. As a general rule, provided there are no contraindications for you to have an epidural, and upon consultation with the midwife and/or obstetrician, you can request the epidural at any stage during the labour.

There may be medical reasons for placement of an epidural such as having high-blood pressure prior to or during labour, the condition known as pre-eclampsia or toxaema, or the need for use of medications that augment and speed up labour due to poor/slow progress.

The other factor that needs to be kept in mind is that usually but not always the length of labour is shorter with each subsequent pregnancy. If this is not your first labour, the window of opportunity may be shorter for the epidural to be inserted and have its effect before delivering the baby. You should discuss the desire to have the epidural with your obstetrician or midwife looking after you at the time of labour. They will be able to advise you on the timing depending on the progress and status of your labour and medical condition at the time.

Will I need to have a caesarean section if I have an epidural?

Not necessarily. Epidural analgesia is not associated with an increased incidence of caesarean section when compared with other methods of pain relief such as morphine or pethidine injections into a muscle. Regional analgesia may be associated with increased duration of the second stage of labour and instrumental vaginal birth (delivery requiring use of forceps), but has no effect on the risk of caesarean section (Obstetric Anaesthesia, Scientific Evidence 2008). Prolonging the second stage of labour poses no significant risk to the mother and baby.

Will an epidural affect my baby?

Epidural analgesia has no effect on the immediate status of the baby. (Obstetric Anaesthesia, Scientific Evidence 2008)

Can epidurals cause back pain?

Epidurals are generally not associated with increased incidence of back pain after childbirth. (McGrady E, Litchfield K, Epidural analgesia in labour, Continuing Education and Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain, volume 4 No 4, 2004)

What are the risks associated with epidural?

Block failure

A retrospective analysis in the United States of 19,259 deliveries showed a failure rate of 12 per cent. (Pan PH, Bogard TD, & Owen MD 2004; Incidence and characteristics of failures in obstetric neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia: a retrospective analysis of 19,259 deliveries, International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 13:227-33).

Post-dural puncture headache

This occurs when the epidural or spinal needle inadvertently breaches the dura mater. Dura is a tissue cover, which surrounds and encases the spinal cord and the bathing cerebrospinal fluid. The spinal fluid leaks out of the hole made in the dura. Dural puncture occurs in approximately 1 per cent of epidural blocks, however, not all patients in whom dura has been punctured develop headaches. (Pan PH, Bogard TD, & Owen MD 2004, Incidence and characteristics of failures in obstetric neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia: a retrospective analysis of 19,259 deliveries, International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 13:227-33).

The likelihood of developing a headache is related to the size of the epidural or spinal needle used as well as the age of the patient, with younger patients having a higher risk. Of the patients that have had an inadvertent dural puncture, more than 50 per cent will develop what is known as a post-dural puncture headache (PDPH). The headache usually develops within 48 hours but may occur later.

The headache is characterised by its onset on assuming an upright position and resolving on lying flat. It is usually a dull, pressure-like headache affecting any part of the skull and can also extend to the neck and upper back. Other symptoms may include mild hearing loss or ringing in the ears, known as tinnitus, as well as double vision and neck stiffness. The headache can be associated with nausea, vomiting and pain in the eyes on looking at the light (photophobia).

Not every headache after labour in women who have had an epidural or spinal block is a post-dural puncture headache. There can be many causes, including tension headache and preeclampsia.

Most headaches will settle within a few days but some may last longer (Thew M, Paech, Jb, Management of postdural puncture headache in the obstetric patient. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology Issue: Volume 21(3), June 2008, p 288-292). Management is divided into conservative and performing epidural blood patch. Your anaethetist will explain and discuss these treatments with you.

Conservative treatment includes bed rest, adequate fluid intake either by mouth or by injection into a vein, and oral analgesic medications. There is low-level evidence of the use of oral and intravenous caffeine (prepared for injection). If this approach fails and or the headache is severe then an epidural blood patch may be considered.

Epidural blood patch is by far the more effective treatment. It usually involves two anaesthetists, one who performs the epidural and the other who collects blood from the same patient. Blood is taken in an extremely sterile way with the arm washed with betadine solution to minimise the chance of contamination. The blood is then injected through the epidural needle. This treatment is thought to “patch” or “plug” the hole in the dura from the original labour epidural, when the blood clots.

Low blood pressure (hypotension)

Blood pressure may drop after the administration of local anaesthetic administered via the epidural or spinal route. For this reason, monitoring of blood pressure and of the foetal heart rate begins immediately prior to performing the epidural or spinal block and continues regularly throughout labour for as long as the local anaesthetic drugs are being given via the epidural.

Temporary leg weakness

Leg weakness is due to the effect of local anaesthetics on nerves controlling the movement of legs. It usually occurs with a prolonged duration of epidural drug administration. The effect is temporary and wears off within several hours.

Fever

Compared with narcotic drugs administered for pain relief, epidural analgesia is associated with up to four times the incidence of fever (temperatures above 38 degrees). It is not known why but is usually of no significance. (Philip J, Alexander JM & Sharma SK 1997, Epidural analgesia during labour and maternal fever, Anaesthesiology 90, 1271-5)

Permanent neurological injury

Neurological (nervous system) injury may include sensory loss, motor weakness and paraplegia. Data from a large recent audit published in British Journal of Anaesthesia in November 2006 showed the incidence of permanent harm (defined as symptoms persisting for more than six months), including death was 0.6 per 100,000 women who had an epidural for labour.

If I had an epidural put in for labour pain, and I require a caesarean section, what happens to the epidural?

Provided that the epidural has been working well and it provided you with adequate pain relief from contractions, it can be used to provide anaesthesia for the caesarean section. However, an epidural for labour pain may not be adequate to provide anaesthesia for surgery because the medications used for labour pain may not have spread far enough to provide pain relief for the surgery. The anaesthetist will assess the adequacy of the epidural and, provided he or she is satisfied, may “top up” the epidural with more local anaesthetic with or without opioid drugs. If this is done it is a different anaesthetic.

How will the anaesthetist make sure that I won’t feel pain during the caesarean section?

There are several ways to test the adequacy of the epidural or spinal block used to achieve an anaesthesia for caesarean section. Firstly, the anaesthetist will ask you to raise your legs one at a time. Known as straight-leg raising, this involves lifting your leg up straight off the bed, keeping the knee straight. In almost all cases of effective block, you should have limited ability to do that. Your legs may feel incredibly heavy, “concrete” like, and you will experience pins and needles. This is all indicative of a successful block. Secondly, the anaesthetist will test the level that the block extends up your body to determine its adequacy for surgery. This is done most commonly using ice. Temperature differentiation is controlled by the same types of nerves as pain transmission, so if you cannot appreciate the coldness of the ice you will not experience pain.

What is the difference between spinal and epidural block?

The terms “regional anaesthesia”, “spinal block” and “epidural block” are often used interchangeably. This is incorrect. Both spinal and epidural block are subsets of regional anaesthetic.

Spinal block differs from an epidural block in a number of ways. Firstly, a smaller needle is used to perform a spinal block than an epidural block. Secondly, the drugs are injected into the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the spinal cord. In order to do that the needle makes a tiny hole in the dura, which is a tissue encasing the spinal cord and the cerebrospinal fluid. Small doses of local anaesthetic are required because they spread more easily in the spinal fluid. With an epidural block, the drugs are delivered outside the dura, in the epidural space, hence the name for the block. Occasionally, the dura can be inadvertently breached in performing an epidural block, known as a dural puncture. Larger doses of local anaesthetic are required because the spread is through tissues rather than fluid. Thirdly, a spinal block is a single injection of local anaesthetic medications and so there is only one opportunity to deliver the medications. With an epidural, a catheter sits in an epidural space so drugs can be delivered as needed to extend the duration of the block. An epidural block can be made to last longer than a spinal block.

[Sourced from the ANZCA here]