This information is only a guide and should not replace information supplied by your anaesthetist. If you have any questions about your anaesthesia, please speak with your treating specialist.

Topics

Anaesthesia for eye surgery

Eye blocks

Anaesthesia for endoscopy and colonoscopy

Anaesthesia for hip or knee replacement

Regional anaesthesia

Spinal block

Analgesia options after surgery

Anaesthesia and children

Pain relief and having a baby

Nitrous oxide

Epidural anaesthesia for pain relief

General anaesthesia for caesarean section

Pain relief after caesarean section

Anaesthesia for eye surgery

Eye surgery can be performed under topical anaesthesia, eye block or general anaesthesia. The choice of anaesthesia depends on the patient, type of surgery and the preference of the eye surgeon.

Cataract surgery can be performed under topical anaesthesia using local anaesthetic eye drops although this does not result in the same surgical operating conditions that can be achieved with an eye block. Topical anaesthesia is commonly used in patients for whom eye block is contraindicated or in rare cases where the eye block fails to provide adequate anaesthesia and analgesia.

Cataract surgery can be performed under topical anaesthesia using local anaesthetic eye drops although this does not result in the same surgical operating conditions that can be achieved with an eye block. Topical anaesthesia is commonly used in patients for whom eye block is contraindicated or in rare cases where the eye block fails to provide adequate anaesthesia and analgesia.

From a medical point of view, the patient should be able to lie flat. Patients with significant heart failure or respiratory disease may not be able to do so. For more information about eye surgery please download this document: Anaesthesia for eye surgery.

Eye blocks

Anaesthetists and eye surgeons can perform eye blocks, which involve one or two injections of local anaesthetic around the eye. Once the local anaesthetic drug begins to work, usually in around 10 minutes, the patient will not be able to see out of the eye or move it and surgery may begin. Once the surgery is complete, the eye will be covered with a patch and will be reviewed the next day.

The risks of the block include eye perforation (less than 1 per cent) and bleeding into the eye (less than 1 per cent). Reaction to local anaesthetic drugs is rare, however swollen red conjunctiva (white part of the eye) is not uncommon.

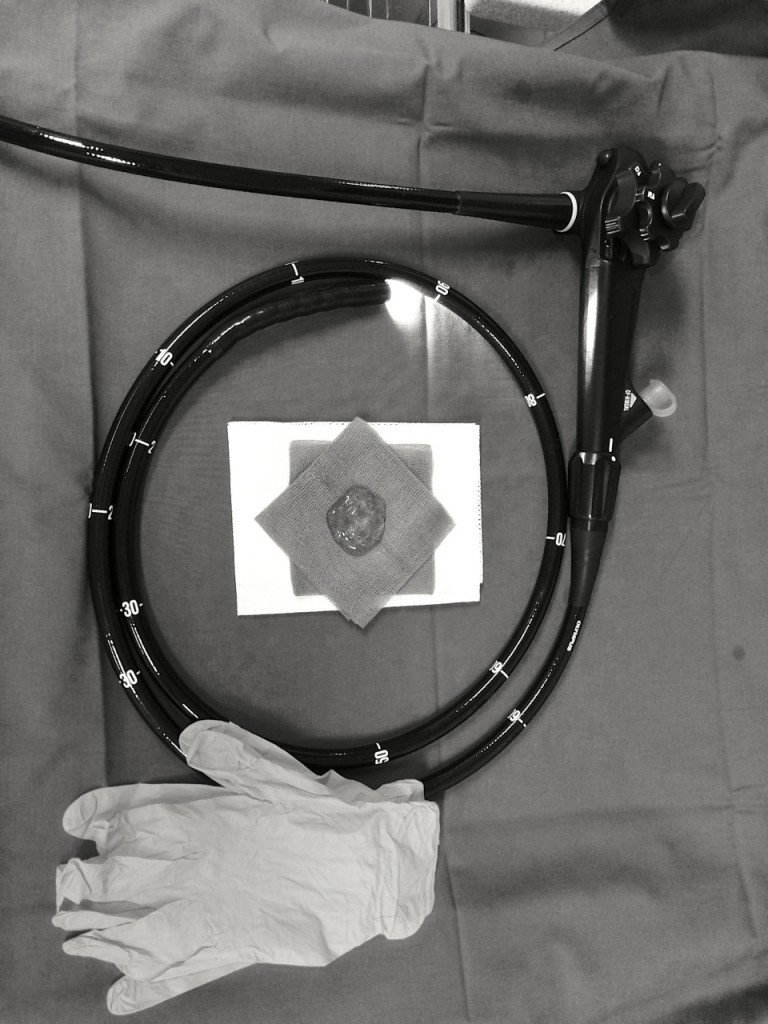

Anaesthesia for endoscopy (gastroscopy or colonoscopy)

Anaesthesia for endoscopy procedures, which includes gastroscopy and colonoscopy, are frequently performed as day-stay cases.

Gastroscopy is a procedure where a flexible tube containing a camera at its tip is inserted via the mouth passing through the oesophagus (the muscular food tube that connects the mouth to the stomach) into the stomach and first part of the small bowel (the duodenum). It is performed to investigate and treat symptoms such as dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), gastroesophageal reflux disease (commonly known as heartburn) and oesophageal and stomach tumours.

Gastroscopy is a procedure where a flexible tube containing a camera at its tip is inserted via the mouth passing through the oesophagus (the muscular food tube that connects the mouth to the stomach) into the stomach and first part of the small bowel (the duodenum). It is performed to investigate and treat symptoms such as dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), gastroesophageal reflux disease (commonly known as heartburn) and oesophageal and stomach tumours.

Colonoscopy is a procedure where a long flexible tube containing a camera at its tip is inserted via the rectum to allow a doctor to visualise the large bowel. It is performed to investigate conditions affecting the large intestine.

Many conditions do not have symptoms at the early stages. Endoscopic treatment is limited and usually involves either removal of polyps or foreign objects. In most cases, patients are given deep sedation. Procedural sedation is administered in order to perform the procedure and aims to ensure patient safety and comfort. For more information about endoscopy please download this document: Anaesthesia for endoscopy.

Anaesthesia for joint replacement

Osteoarthritis is not uncommonly found in hips and knees, and patients undergoing hip or knee replacements are generally elderly. This means that a large proportion of hip or knee replacement patients have significant co-morbidity, with 40 per cent of those presenting for joint replacement being treated for high blood pressure or heart problems (Connolly D, State of the Art: Orthopaedic Anaesthesia, Anaesthesia 58: 1162-1203, 2003).

Many joint-replacement patients also have undiagnosed heart problems and will require further assessment and investigation. Most patients undergoing joint replacement will accept the risks involved because of the potential improvement in their quality of life.

Many joint-replacement patients also have undiagnosed heart problems and will require further assessment and investigation. Most patients undergoing joint replacement will accept the risks involved because of the potential improvement in their quality of life.

Pain relief options aim to provide optimal pain relief while minimising side effects such as sedation, post-operative nausea and vomiting, and leg weakness (Grant C Checketts M, Analgesia for primary hip and arthroplasty: the role of regional anaesthesia. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care and Pain, Vol 8(2), 56-61, 2008). Regional anaesthesia can achieve those aims. For more information about joint replacement surgery please download this document: Anaesthesia for joint replacement surgery.

Regional anaesthesia

Regional anaesthesia is an umbrella term used to describe nerve blocks, epidural block and spinal blocks.

Both regional anaesthesia and general anaesthesia have their advantages and disadvantages. Regional anaesthesia may offer better pain relief after the operation, it is associated with less blood loss during the operation and there is less risk of developing a deep venous thrombosis in patients who receive spinal or an epidural block.

Regional anaesthesia may be used alone or in combination with conscious sedation or general anaesthesia. Patients may not receive a spinal or an epidural block if:

- They are taking blood thinning medications, clopidogrel (have stopped taking it for less than seven days), warfarin, or their INR >1.4. (Please note: Patients must receive specific instruction from their heart specialist or anaesthetist before they stop taking any medications).

- They have a systemic (blood) infection or infection at the site of possible spinal or epidural insertion in the back.

- They have a low platelet (blood clotting) count. Alternatively, a general anaesthetic may be used alone or in combination with a nerve block. Nerve blocks

Spinal block

Spinal blocks (also known as central neuraxial blocks) involve the insertion of a fine needle through the skin of the back into the cerebrospinal fluid and injecting local anaesthetic (sometimes in combination with other medications). The injected medication spreads within the spinal fluid surrounding the spinal cord to block conduction of the nerves. This form of neuraxial block (injection into the fluid around the spinal cord) generally works faster than epidural blocks with the legs becoming weaker and heavier more quickly. The dose of local anaesthetic for spinal blocks is much smaller than that for epidural blocks. These effects may last for several hours.

Side effects and complications of spinal blocks include:

- Low blood pressure (hypotension).

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Post-dural puncture headache (for further information see epidurals and childbirth).

- Unexpected high block that can lead to low blood pressure and weakness of respiratory muscles in the chest.

- Total spinal where the local anaesthetic spreads up to the fluid bathing the brain leading to the above effects on blood pressure and breathing, as well as unconsciousness.

- Neurological sequlae where there may be nerve damage, either temporary or permanent.

- Seizures or fits, which may arise if local anaesthetics are inadvertently introduced into the blood stream.

- Failed spinal and failed epidural are not side effects or complications, however, if for any of a number of reasons the local anaesthetic does not achieve the intended outcome the block is termed a failed block.

Most commonly, epidurals in the obstetric setting are performed for labour pain. They may be used to provide anaesthesia for a caesarean section if that becomes necessary.

Most commonly, epidurals in the obstetric setting are performed for labour pain. They may be used to provide anaesthesia for a caesarean section if that becomes necessary.

In the obstetric setting, spinal blocks are most commonly performed to achieve anaesthesia for a planned caesarean section. Rarely, a spinal block may be used to provide effective, although time-limited, pain relief for labour when spontaneous vaginal delivery is anticipated (Obstetric Anaesthesia: Scientific Evidence, 2008). Some anaesthetists perform both a spinal and an epidural block for either labour pain or a caesarean section. This is called a combined spinal epidural (CSE).

CSE has a slightly faster onset of pain relief from time of injection. There is no difference in satisfaction, mode of birth and incidence of post-dural puncture headache or baby outcome. (Obstetric Anaesthesia: Scientific Evidence, 2008).

Analgesia options after an operation

Different anaesthetists and hospital-based acute-pain service teams have different protocols on providing effective pain relief after joint replacement. Patients who require further information should consult their anaesthetist.

Multimodal analgesia

Multimodal analgesia combines different classes of medications that work in different ways to achieve optimal pain relief. Multimodal analgesia is a cornerstone of an effective pain-relief plan. It is important that some of these medications are given regularly, for example, combining paracetamol with non-steroidal drugs such as Voltaren. A multimodal approach reduces the likelihood of breakthrough pain, which may occur when the pain relief lasts for less time than the pain.

Patient-controlled analgesia

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is an effective postoperative analgesic technique that enables patients to control their own analgesia in a regimen determined by their medical practitioner.

A dose of drug, such as morphine or fentanyl, is delivered as demanded by the patient via a syringe pump connected to a cannula or tube that is inserted into a vein but with the built-in safety feature where the pump will not deliver medication after the previous dose for an interval that is pre-determined by the pain physician/anesthetist. The patient activates the delivery of the bolus (single) dose of the medication by pressing a button or similar device.

A dose of drug, such as morphine or fentanyl, is delivered as demanded by the patient via a syringe pump connected to a cannula or tube that is inserted into a vein but with the built-in safety feature where the pump will not deliver medication after the previous dose for an interval that is pre-determined by the pain physician/anesthetist. The patient activates the delivery of the bolus (single) dose of the medication by pressing a button or similar device.

Usually the interval between subsequent doses is set to five minutes. This is the lockout interval during which no drug is delivered if the patient pushes the button, however the attempt is registered on the machine. The technique is safe because when patients are sedated and comfortable, they are either unable to push the button or don’t need to push the button and so will not receive excessive doses.

Patients on a PCA are monitored by nursing staff, who record vital signs, breathing rate, pain and sedation to ensure the PCA is used appropriately, is effective and safe. A doctor will review the patient’s pain and pain relief to determine when it is appropriate to cease the PCA. Appropriate pain-relief medication will be prescribed once the PCA is removed.

When a patient recovers from the postoperative pain for which the PCA was prescribed, they may be given tablets to help manage any pain. Tablets may be prescribed to be taken regularly or they may be prescribed “as needed” (known as a PRN). This means the medication will be given when the patient advises the nursing staff that they are feeling pain.

Nerve blocks

Anaesthetists may perform nerve blocks in combination with a general anaesthesia to reduce the severity of post-operative pain.

Nerve blocks include femoral nerve blocks for hip or knee surgery, or sciatic nerve blocks in combination with femoral nerve blocks for knee surgery.

Nerve blocks involve injecting local anaesthetics around the nerves that transmit pain. Nerves may be localised using an ultrasound or a device called a nerve stimulator. The nerves are then transiently anaesthetised for a period of time (up to one day) after which they regain their function.

Anaesthesia and children

Anaesthesia is relatively safe and can be given to children of all ages, including newborn babies.

It can be more difficult to anaesthetise the very young and those with underlying congenital illnesses (illnesses that are present at birth) and not every hospital has the appropriately trained staff and equipment to anaesthetise and operate on children. Some hospitals will not accept children younger than a certain age while other hospitals do not perform surgery on children at all.

Children who are very young (less than 12 months old), have complex medical illnesses or who require major surgery for conditions, such as scoliosis, will be referred to the children’s hospital in the nearest city. Other hospitals and day-surgery units accept children for routine operations such as tonsils, grommets (tubes in the ear to assist hearing) and dental surgery.

Children are usually anaesthetised in a different way to adults. If an older child is prepared to have a tube inserted into a vein, known as a cannula, they are anaesthetised via an intravenous injection into the tube. A topical anaesthetic cream can be applied to the arms to numb the skin so inserting the cannula is painless.

Children who don’t wish to have a cannula may be anaesthetised via a mask delivering an anaesthetic vapour or gas. The procedure is painless but children can sometimes find the experience unpleasant because they are unfamiliar with the people and the environment and may find the mask, which is gently put on their face, intrusive and scary. This experience has no long-term detrimental effects and after breathing through the mask, it takes a few minutes for the child to lose consciousness and be anaesthetised.

Parents may be allowed to remain with their child as he or she is anaesthetised depending on the circumstances. Discuss this option with the anaesthetist. As the child breathes the gas and loses consciousness, his or her eyes may assume strange positions, such as rolling back. This is normal. They may snore or move their arms or legs – this is a transient happening that occurs as the child moves through different stages of sleep. After the child is anaesthetised, parents will be asked to leave the operating room or the anaesthetic bay.

Once the surgery is finished and the child is awake in the recovery room, parents may be called to be with them. Often a child will cry upon waking from an anaesthetic and there are multiple causes for this, including waking in an unfamiliar environment, pain and sometimes “emergence delirium” (confusion), which can be caused by anaesthetic gas. Children with this condition may be agitated, restless and confused. The condition resolves and improves with time, but may need an anaesthetist to administer medication to settle the child. For more information about anaesthesia and children please download this document: Anaesthesia and children.

Pain relief and having a baby

Labour is among the most painful human experiences. The cause of labour pain is multifactorial and includes stretching of the cervix during dilatation in the first stage of labour, and stretching of the vagina and perineum in the second stage of labour. Anaesthetists play an important role in providing pain relief and facilitating delivery of the baby. A common form of pain relief for labour is by epidural. For further information see epidural and childbirth.

It is advisable for pregnant women to discuss the methods of pain relief with the midwife, obstetrician or anaesthetist well in advance of their labour.

Should pregnant women need to have their babies delivered by caesarean section, (an operation where the baby is delivered via an incision in the abdomen) which may be advised or required for medical reasons, the anaesthetist will provide the most appropriate form of anaesthesia. This may be either regional anaesthesia in the form of a spinal block, an epidural block, or a combined spinal-epidural block, or general anaesthesia.

Epidurals are the most effective method of pain relief for labour and require the services of an anesthetist. Some pain relief alternatives, such as medications given by injection, do not require the services of an anaesthetist but will be prescribed by a doctor. For more information about pain relief when having a baby please download this document: Pain relief and having a baby.

Nitrous oxide

A mixture of nitrous oxide (N20) with oxygen can be self-administered by a woman who is in labour. About 85 per cent of women find it helpful, although few find it adequate as the only means of pain relief. Nitrous oxide is an analgesic and is relatively safe during labour when mixed with oxygen.

A mixture of nitrous oxide (N20) with oxygen can be self-administered by a woman who is in labour. About 85 per cent of women find it helpful, although few find it adequate as the only means of pain relief. Nitrous oxide is an analgesic and is relatively safe during labour when mixed with oxygen.

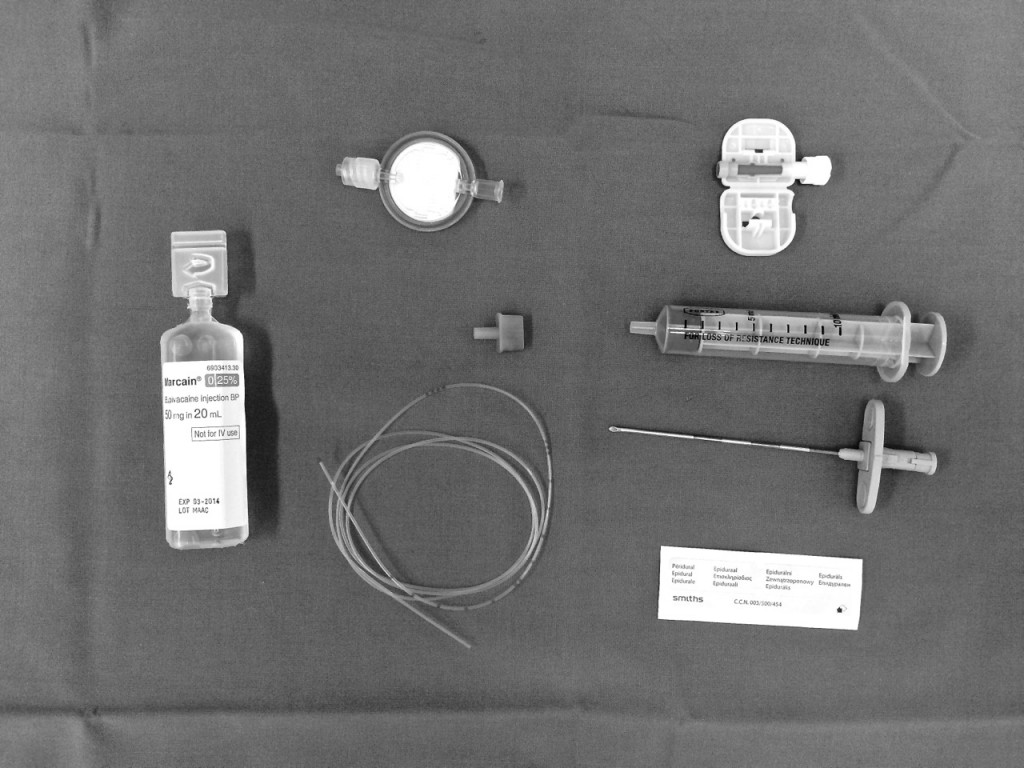

Epidural anaesthesia for pain relief

Epidural and spinal analgesia/anaesthesia (also called central neuraxial analgesia/anaesthesia), where local anaesthetic with or without opioid is administered around the outer coverings of the spinal cord or into the fluid bathing the spinal cord, is the most effective relief available for labour pain.

Epidural and spinal anaesthesia may be performed with patients in the sitting position or lying on their side depending on the anaesthetist’s preference. After washing the back with antiseptic solution local anaesthetic is injected under the skin to reduce discomfort that may be felt from passage of the epidural needle.

Epidural and spinal anaesthesia may be performed with patients in the sitting position or lying on their side depending on the anaesthetist’s preference. After washing the back with antiseptic solution local anaesthetic is injected under the skin to reduce discomfort that may be felt from passage of the epidural needle.

Patients are positioned with a curved back posture, typically described as making the shape of the Sydney Harbour Bridge or an angry cat. By placing the chin on to the chest and dropping the shoulders, the space between the vertebrae increases to allow passage of the epidural needle. A fine plastic tube known as an epidural catheter may be threaded through the needle, after which the needle is removed.

The epidural catheter sits in the epidural space outside the spinal cord and the spinal fluid. Local anaesthetics can be administered via this catheter to block transmission of pain along the nerves coming from the womb and cervix. Medications may be administered as a continual flow through the epidural catheter throughout the labour or by a midwife injecting the prescribed dose into the epidural catheter.

The time taken to perform the procedure depends on issues such as the shape and curve of the patient’s spine and whether the patient is overweight. It may take between five and 30 minutes to perform, with the onset of pain relief starting within five minutes of the patient receiving the local anaesthetic.

For further information about side effects and complications of epidural anaesthesia, see epidurals and childbirth

General anaesthesia for caesarean section

General anaesthesia is uncommonly performed these days for caesarean section. When it is used, the reasons include:

- An emergency caesarean section, where there is no time to perform a spinal or an epidural block.

- Maternal preference.

- Failed spinal or epidural block (about one in 100).

- Reasons for not for performing spinal or epidural block may include:

- Patients taking antiplatelet (clotting medication) or anticoagulant (blood thinning) drugs, for example, clopidogrel, clexane, warfarin).

- Systemic (in the blood) infection, also known as sepsis.

- Toxaemia (an abnormal condition) of pregnancy (pre-eclampsia) with high blood pressure and where clotting factor activity may be impaired.

- Severe bleeding with low blood pressure

The relative risk of problems during general anaesthesia for caesarean section appears to be higher than for neuraxial block, and may include airway problems (one in 300) and inhaling gastric contents into the lungs.

Pain relief after caesarean section

Postoperatively there are numerous options available to assist with pain control. Typically, in the absence of contraindications, patients may be prescribed simple analgesics such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) such as diclofenac (Voltaren) to be administered regularly during the first few days. Pain relief options depend on the form of anaesthesia and analgesia used for the caesarean section.

Epidural top up

Anaesthetists may administer opioids such as morphine or pethidine via the epidural catheter once the baby is delivered or at the end of the caesarean section. These medications assist in providing effective pain relief for the next 24 hours or so. After this, other oral opioid medications, such as oxycodone, can be used. A potential side effect of having epidural opioids includes pruritus (itchy skin), nausea and vomiting. Patients not given epidural morphine or pethidine may be prescribed oral medicines such as oxycodone or what is known as patient controlled analgesia (PCA). For further information see patient-controlled analgesia.

Spinal block

Apart from local anaesthetic drugs, which provide excellent anaesthesia for labour pain and caesarean section, the anaesthetist may choose to add an opioid, or medications such as pethidine or fentanyl, to the spinal mix. This may provide effective analgesia lasting into the next day. Potential side effects of spinal opioids include pruritus (itchy skin), nausea, and vomiting. Patients who do not receive spinal opioids may be prescribed oral medicines such as oxycodone or may be prescribed medications to be delivered by PCA pump. For further information see patient-controlled analgesia.

General anaesthesia

Where general anaesthesia has been used for caesarian section the options for pain relief include oral opioid medications such as oxycodone or use of PCA. For further information see patient-controlled analgesia

Systemic analgesics

Intramuscular morphine or pethidine given by injection reduce but may not eliminate the experience of pain. If given in multiple doses and/or prior to delivery of the baby, they can cause breathing suppression in the baby. Should this occur there are antidotes available to assist the baby.

[Sourced from the ANZCA here]